Let’s talk about Colonial Gothic Fourth Edition. It’s off to the printer! If all goes well, Backers will have their print copies before July 2025. The dice? They’ll be ordered soon. And the Companion book is almost done. Last week, all Backers got their PDF copies. It’s great to see that all the hard work is paying off.

That out of the way, I want to talk about rule choices.

Gamers love to debate choices. It’s part of the fun. Put a rulebook before us; you can bet a discussion will break out. It’s what we do.

Let’s dive into the 12° mechanic. It drives both Colonial Gothic and Shadow, Sword & Spell. Here’s how it works: roll 2d12, add or subtract your bonus or penalty, and see if you meet or beat the Target Number.

Easy. As. That.

So, why did I change the 12° mechanic? I eliminated the wide range of Target Numbers from the Third Edition. The old version had Target Numbers from 2 to 42. The new edition has just three: 6, 12, and 24. That’s it.

Tests in the new edition still work the same way. Add or subtract a bonus or penalty to the roll and adjust for your Skill. The only change is how Abilities work. Now, they use a ± sign. For example, Vigor might be +1, and Reason could be -2. Just adjust your Attribute when you take a Test.

Here’s a simple formula to remember:

Governing Attribute + Rank in Skill ± Bonus/Penalty + 2d12 ≥ Target Number (TN) = Success

Straightforward.

For Colonial Gothic, the universal Target Number is TN 12. That’s the number used for all Tests to judge success. Why is TN 12 the universal Target Number?

I am going to get a little philosophical.

Life.

Yep, life. It’s a 50/50 game. You have a 50/50 chance of falling when walking up or down the stairs.

And when crossing a street or riding your bike? Same deal—50/50 chance of getting hit by a car!

Falling in love? 50/50 chance.

Life is random for me. No matter how you plan or prepare, you always have a 50/50 chance of succeeding or failing if you are a pessimist.

But here’s the twist: what you’re doing changes those odds. If you carry a stack of boxes on the stairs, your chances of falling go way up.

So, let’s dive into some math!

No, come back; this will not be so bad.

I hope.

The Risk of Falling While Carrying 100 lbs of Boxes Up and Down the Stairs

Carrying boxes up or downstairs might not seem like a big deal, but it is risky. Let’s say you carry a number of boxes weighing 100 lbs. Your balance is off, you can’t always see where you’re going, and reacting quickly is hard. All that makes falling way more likely—especially on a 12-step staircase. To better understand how risky it is, we use two probability models: one that works with percentages and another that simulates the odds using 12°. Both give us a clearer picture of the chances of taking a tumble.

What Makes Carrying Boxes Down Stairs So Risky?

Carrying 100 lbs of boxes downstairs is a recipe for disaster for several reasons. First, the extra weight affects your balance and makes it harder to adjust if you lose footing. On top of that, if your vision is obstructed—say if the boxes block your view—it’s much easier to make a wrong step and fall. Let’s not forget fatigue and the strength of your grip; holding something heavy wears you out quickly, reducing your ability to correct a slip. Environmental factors play a role, too. Poor lighting, slippery steps, or a lack of handrails can significantly increase the likelihood of falling. So, taking all these elements, it’s clear that carrying heavy boxes down a staircase is risky. Let’s use these two methods to simulate the situation and estimate the probability of falling.

Two Ways to Calculate Fall Probability

Here are the two models:

Percentage-Based: Assign a percentage chance of falling per step and calculate the likelihood of falling at least once over 12 steps.

12°: This is how 12° works, and it assumes you need to beat or meet a Target Number of 12.

Simulation Results

Ok, after I ran 100,000 simulations, here are the following probabilities:

Even something small increases your likelihood of falling over 12 steps. Since risk builds with each step, the chance of at least one fall is extremely high in most cases.

How Probability Builds Up Over Steps

The probability of falling at least once over 12 steps uses this formula:

Huh? How does this work?

The formula shows how the chance of falling increases over each step you take when there is a chance of falling on each step.

Breaking It Down

An Example

Suppose the probability of falling on a single step is 20%.

This means there’s a 93.13% chance of falling at least once over the 12 steps, even though each step only had a 20% chance of causing a fall.

The Key Takeaways

Even small difficulties greatly increase the likelihood of falling over 12 steps. Since risk builds with each step, the chance of at least one fall is extremely high in most cases.

Comparing the Two Probability Models

So, how does a percentage-based model compare to a 2d12-based model?

Great question!

A percentage-based model assigns a fixed risk per step, showing how small risks accumulate over multiple steps. Whether you walk up or down, every step you take is a risk. This approach is more accurate for the real world, where you can balance and move as you descend.

On the other hand, 12° uses dice rolls to simulate real-life randomness. Each modifier, ranging from −1 to −6, represents this added difficulty. The model highlights how a single unlucky roll can lead to failure. For 12°, this allows for the unpredictable outcomes I want.

Visualizing the Risk

Fall Probability per Step

This graph shows that your likelihood of falling on one step increases with different difficulty conditions. The harder the conditions, the higher the per-step risk.

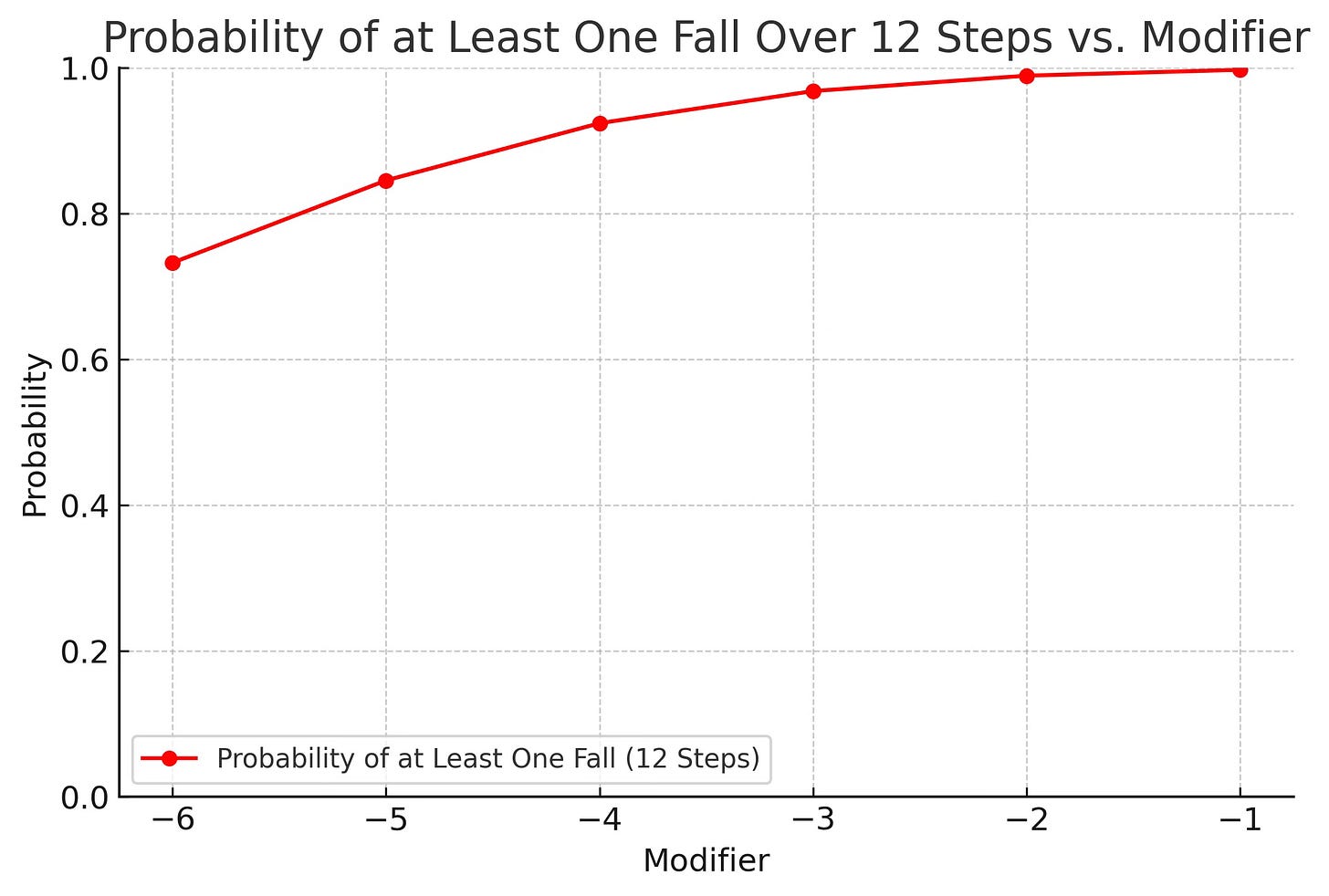

Probability of at Least One Fall Over 12 Steps

This graph demonstrates how your fall risk builds up over multiple steps you take. Even with moderate per-step failure rates, the overall risk over 12 steps becomes dangerously high.

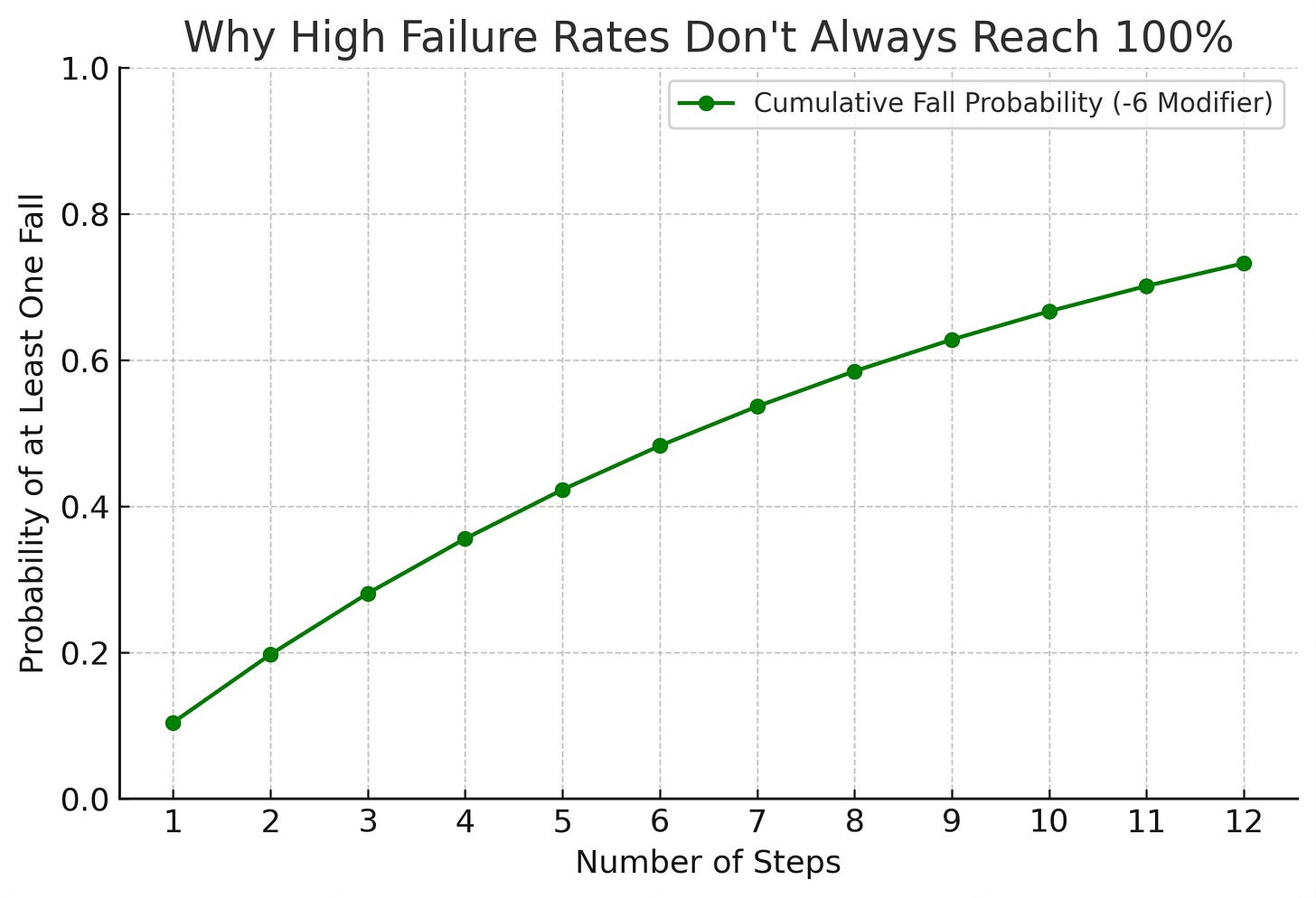

Why High Failure Rates Don’t Always Reach 100% Over 12 Steps

This graph explains why high per-step failure rates don’t always result in 100% falls over 12 steps. Life is random, meaning there is always a small chance of avoiding a fall. If you use a modifier of −6, the chance of falling at least once is lower than you might think. Each step does carry a high risk, but there’s still a small chance you can avoid falling altogether over 12 steps. The risk of failure can approach 100% but doesn’t quite reach it.

Final Thoughts

Carrying 100 lbs of boxes down 12 steps is extremely risky1. Whether you use the percentage model or the 2d12 simulation, both methods show that the odds of falling are very high.

I might not be a doctor, a kinesiologist, or a physical therapist, but if you ever need to carry something heavy downstairs, here’s how to lower your risk:

Take multiple trips instead of carrying too much at once.

Use handrails whenever possible to help with balance.

Make sure stairs are well-lit and clear of obstacles.

Distribute weight evenly to avoid sudden shifts in balance.

Also, you might think twice before carrying 100 lbs of boxes up or down stairs.